Third-Party JavaScript Development: The Future!

Posted by Mike Pennisi

I’ve just returned from the future, and I have a lot to share with you. World news, sports scores, market changes, all that stuff can wait. First, we need to talk about third-party JavaScript.

There’s a great deal of browser technology on the way that will affect the way you write code. Here, I’ll focus specifically on tech that has relevance to third-party JavaScript (3PJS) developers. I’ve editorialized a bit, but this is based on my understanding of how the technology is currently described. To help you out, I’ve tried to keep my own opinion quarantined within sections titled “Recommendation”, and I’ve included references to the official W3C specifications.

Update August 2012 I’ve included a polyfill for the iframe[srcdoc]

attribute. Thanks to commenter Corey Goldfeder for

suggesting the fallback that makes this possible in today’s browsers.

Contents:

- Style

scopedattribute - iFrame

sandboxattribute - iFrame

srcdocattribute - iFrame

seamlessattribute - Content Security Policy

Style scoped attribute

What is it?

- The spec: http://www.w3.org/TR/html5/the-style-element.html#attr-style-scoped

- Support: Chrome 19, via flag (source, see also this section in the Wikipedia article comparing layout engines)

This is a method for limiting the effect of styling to the element it is defined within. It is used like so:

<div class="container">

<style scoped>

p { color: red; }

</style>

<p>This paragraph has red text.<p>

</div>

<p>This paragraph does not.</p>

In today’s (hoverboard-free) world, all the text in the example before would be

rendered in red. In the future, the “scoped” attribute on the style tag will

limit the effect of the tag to its siblings.

Why is it relevant?

Some applications may programmatically append <style> elements to the

publisher’s page. In these cases, there is a danger that the new rules

unintentionally affect publisher content. By utilizing the scoped attribute,

applications can prevent this unfortunate side-effect.

Recommendation

This functionality isn’t backwards compatible, so you’ll break pages on “old” (by tomorrow’s standards) browsers. To use in production, a JavaScript polyfill is completely necessary.

I would normally endorse using the feature anyway (in order to reap the

benefits in supporting browsers). Unfortunately, in order to properly “opt in”

to this behavior, your code will need to do more than just declare the scoped

attribute. Similar content in disparate locations will require duplicate style

elements. It seems somewhat unreasonable to implement such a large change for

the limited reward (avoiding an unlikely side-effect in some future browsers).

All in all, I’d say, “Don’t bother.” Stick with namespacing your ID’s and class

names; for example, use .widgetname-container in place of simply .container.

iFrame sandbox attribute

What is it?

- The spec: http://www.whatwg.org/specs/web-apps/current-work/multipage/the-iframe-element.html#attr-iframe-sandbox

- Support: IE10, Chrome 17+, Safari 5+ (source)

This attribute will enable fine-grained control over the capabilities of a

document housed within an iFrame. Simply declaring the sandbox property

(with no value) on an iFrame will prevent:

- the execution of any JavaScript included within

- the submission of any forms

- the creation of new browsing contexts

- the navigation of the top-level document

- access of other content from the same origin (by forcing the content’s origin to a unique value)

You may selectively grant privileges by setting the attribute’s value to one or

more (space-separated) of the following strings: allow-scripts,

allow-forms, allow-popups, allow-top-navigation, and allow-same-origin.

Why is it relevant?

The main benefit of this feature is security. How you understand (and advertise) this benefit depends largely on how your application is distributed.

If publishers include your application via an iFrame, they have control over

the sandbox attribute. This lets them more easily reason about the security

risks of including your application. For smaller third-parties (or larger

publishers) this will make adoption much easier.

If publishers include your application via a script tag (admittedly far more

common), the benefit will be less apparent to the publisher. In these cases,

your script is still capable of doing any number of dumb things. But, as the

application developer, you can choose to include user-generated content in

sandbox‘d iFrames. This alleviates many vectors of attack from end users

(although, again, it says nothing about the security of your application

itself).

Recommendation

As of today, there is no substitute for sanitizing user input. Browser support is not nearly high enough to consider this measure alone sufficient. That said, defense in depth is an important aspect of any security strategy. If you your app could benefit from the sandbox attribute, I’d say, “Go for it.” Newer browsers will benefit from the feature, and old ones will be no worse off for it.

iFrame srcdoc attribute

What is it?

- The spec: http://www.whatwg.org/specs/web-apps/current-work/multipage/the-iframe-element.html#attr-iframe-srcdoc

- Support: No current browser (IE9, Chrome 18, Safari 5.1, FireFox 12, Opera 11.6), but implemented in WebKit and available in Chrome 20

Years from now, we are using this method to declare the HTML content of an iFrame. This will be accomplished by specifying the content as an attribute of the iFrame itself:

<iframe srcdoc="<p>Potentially-dangerous user content<script>alert('lol');</script></p>"></iframe>

Why is it relevant?

By including HTML inside a “sourceless” iFrame (as opposed to emitting it in

the publisher’s document directly), you can prevent that content from breaking

the surrounding structure (imagine what user-generated content like Hello,

world</div></div></div></td></tr></table> could do to the rest of the page).

This makes sanitization easier. Instead of escaping HTML, potentially

white-listing certain tags (i.e. <b> and <i>), and ensuring that all open

tags are closed, you only have to escape the quotation mark character.

This functionality in combination with the sandbox attribute will also make

preventing JavaScript-based shenanigans easier.

Recommendation

If you’re anything like me, you probably need a minute to recover from a deep-seated nausea resulting from seeing markup in an attribute. Stick with me for a minute–there’s a valid use case here: you have a string of user-generated markup you’d like to display, and you want to associate it with a specific iFrame element.

The practicality of this approach lives and dies on browser support. Most

current browsers completely ignore this attribute, resulting in an unacceptable

experience. For this reason, I recommend holding off on using srcdoc for

now.

If you want access to this functionality now, check out the following polyfill, which leverages script-targeted URLs in unsupporting browsers:

iFrame seamless property

What is it?

- The spec: http://www.whatwg.org/specs/web-apps/current-work/multipage/the-iframe-element.html#attr-iframe-seamless

- Support: No current browser (IE9, Chrome 18, Safari 5.1, FireFox 12, Opera 11.6), but functional in Chrome 21

The seamless property is declared on an iFrame like so:

<iframe src="https://bocoup.com" seamless></iframe>

It instructs modern browsers to treat the iFrame’s content more like inline markup than it would otherwise. Specifically, this means:

- Hyperlinks navigate the parent context

- The parent’s stylesheets cascade in (importantly, the inverse is not true)

- More “neutral” rendering, ie:

scrolling="no" marginwidth="0" marginheight="0" frameborder="0" vspace="0" hspace="0"

Why is it relevant?

The seamless property will allow you to deliver a more intuitive experience

to your users because links function as they’d expect. Furthermore, it will

allow you to inherit the publisher’s styling, making a more natural

integration possible.

Recommendation

This feature shares many of the benefits of the proposed scope attribute for

<style> tags, but won’t break publishers’ pages in older browsers. This is

not to say it is backwards compatible per se: older browsers will not cascade

the publisher’s stylesheets into your iFrames. Keep it on the radar, but it may

be best to wait for the time being.

Content-Security Policy

What is it

- The spec: http://dvcs.w3.org/hg/content-security-policy/raw-file/tip/csp-specification.dev.html

- Support: Chrome 16+, FireFox 11+ (incomplete) (tested with the CSP Readiness suite by Erlend)

I saw strange and wonderful things on my trip the future. Jet packs. Astronaut food. Dogs and cats living together. Content-Security Policy easily stands out as the most important.

At a high level, Content-Security Policy is a method for specifying from where remote content may be included in a document. It is specified before the document is first rendered–either by a new HTTP header:

Header: `Content-Security-Policy`

…or a <meta> tag in the document head:

<meta http-equiv="content-security-policy"></meta>

Upon receiving this information, compliant browsers will ignore all resources not explicitly white-listed.

The white-list is largely specified on a per-domain basis, but CSP supports

keywords as well: 'self' (same origin as website), 'none' (disallow all

sources), 'unsafe-inline' (inline script and/or style tags, 'unsafe-eval'

(runtime code evaluation via eval, setTimeout, setInterval, and

Function).

Back-end devs will definitely want to read up on the spec concerning implementation details.

Why is it relevant?

In general, CSP will give publishers a method to prevent a broad range of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. (The developers at Twitter have written about their early impressions implementing this technology here.)

This is of particular interest to third-party application developers because we largely traffic in cross-site scripting patterns.

If your application displays user-generated content (a comment system, for example), and users may inline images (or any resource for that matter), you will need to host the images yourself. This is because publishers may disallow resources from arbitrary locations on their pages.

Bookmarklets will also be affected. The spec is very clear that bookmarklets

themselves should not be subject to a document’s CSP. This is a good thing,

because we all love bookmarklets, and constraining them in this way would

likely kill them. It’s not all fun-and-games, though. Many bookmarklets rely on

injecting img and script tags into the document. For example,

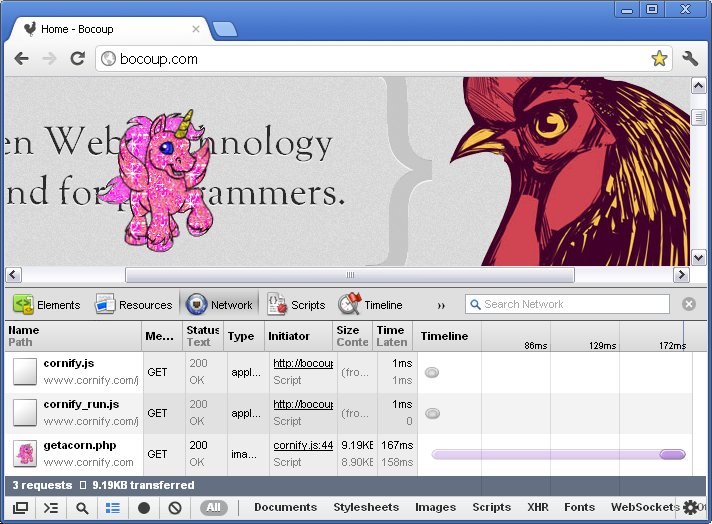

the Cornify bookmarklet injects two scripts and an

image from the cornify.com domain:

This behavior will no longer be generally achievable on all websites as more and more pages disallow willy-nilly image and script loading.

Most of these restrictions translate to more work for the 3PJS developer. There is one security benefit that we get for free, though: our applications will no longer be tools for DDoS attacks.

Consider the following line of code:

new Image().src = "http://zombo.com?" + new Date().getTime();

If an attacker managed to sneak this into your app, then every user across all publisher sites would make that request with every page load. When more publishers enforce a Content-Security policy, most of these requests will not be issued in the first place.

Admittedly, I have yet to hear of this attack actually being carried out. But it’s nice to know that 3PJS developers can claim some benefit (however inconsequential) from CSP.

Recommendation

As publishers begin implementing this security feature, they are going to expect a rigorous list of domains required by your application. You’ll need to inspect your application and note exactly from where it loads resources. There are two ways to do this: bottom-up and top-down.

First off, you’ll want to audit your code base and create a list of the domains that external resources are loaded from.

Next, if you do not already run a “dummy” publisher site for in-house development, get to work! (The utility of such a staging environment merits a dedicated article, this is just one use.) Activate CSP on that site, and use its built-in “reporting” functionality to help identify possible oversights in your initial investigation.

During this auditing process, keep an eye out for inline resources (JavaScript,

CSS, etc.) and “eval-like” patterns (described by the spec

in this section

). You will be hard-pressed to convince some publishers to whitelist

'unsafe-inline' and 'unsafe-eval' just to get your application running. In

this way, you can view following best practices as having direct business

value. (It’s true that in some cases, inline scripts are the most efficient way

to get things done. For what it’s worth, I personally believe that tradeoffs

between speed and security are rarely relevant in front-end development. This

is a sign that CSP is making the web a stronger platform overall.)

After your audit is complete, you should update the documentation you distribute to publishers. While it’s generally in your interest to write these rules as strictly as possible, you can easily paint yourself into a corner. Try to recognize the areas you may need to grow (for example, future subdomains), as there will always be friction in getting publishers to change their policies.

The Future is Cool

The novelty and promise of Third-Party JavaScript are clearly reflected in these far-reaching changes that I witnessed while time travelling. Like with any browser tech, there is a bit of a waiting game we have to play while support catches up. Nevertheless, I feel that it’s in your best interest to have a general idea of the up-and-coming technology.

This is certainly not to say I’ve addressed it all. I welcome any insight into other developing standards that I may have overlooked. If you know of any, please share in the comments!

Hopefully I have not created any temporal paradoxes by telling you all this.